04 Feb Ruins of the Playa Grande Sugar Mill

Many thousands of visitors come each year to the island of Vieques, a short flight or ferry ride from the east coast of Puerto Rico. Most, however, do not venture farther than the stunning beaches or the world-renowned bioluminescent bay. But hidden in the lush jungle foliage to the southwest are the remarkable remnants of a lost community surrounding the ruins of the island’s largest sugar mill. The houses of Playa Grande were largely ramshackle wood-framed, tin roofed structures—all were bulldozed to the ground after the U.S. Navy claimed the land in 1942.

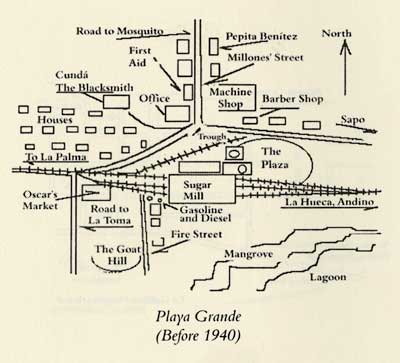

There is little evidence to be found today of the once-vibrant community (see the plan of Playa Grande to the right). But the dilapidated concrete and rusting iron remains of the Playa Grande Sugar Mill may be explored today, perhaps including some elements dating as far back as the hacienda period of the 1840s.

The first impression of the extensive central (sugar mill) ruins—where the light filters down dramatically through the tall trees and the partially-collapsed roofing—may be to compare them to the exotic vine-enveloped temples from the Tomb Raider movies. Ruins speak to us about the fragility of all our endeavors. The burgeoning green jungle embracing and deconstructing the brick walls points out the hubris of our human intentions. It is natural to see these as romantic jungle ruins.

However, a deeper dive into the history of Playa Grande reveals a much darker story, beginning with the horrific abuse of the sugar industry’s laborers, and ending with the dispossession and the forced erasure of the entire community.

The town of Playa Grande no longer exists. You will not find it on any modern map of Vieques. For a visitor to the island today, “Playa Grande” refers only to the picturesque and isolated mile-long stretch of beach accessible by the road heading west from Esperanza.

The town, however, may be noted in the center left segment of the 1946 Vieques map detail, shown above. This barrio, with its rutted dirt roads, developed around the sugar mill of the same name and provided housing for its laborers, machine operators, locomotive engineers, and their families. There was a barber shop, a blacksmith, two markets, a dispensary, and (tantalizingly for this author) a photographer’s shop. On “millones street” were the more substantial homes of the well-to-do, the mill’s managers and foremen.

Drag within the image to rotate the view inside the boiler house. Look upwards to note the largely collapsed roofing. Click the “full screen” button for the most detail.

At the beginning of the 20th century Vieques had four sugar centrales: the Santa María, the Arcadia, the Puerto Real (in Esperanza), and the Playa Grande. Expanding upon an earlier sugar plantation (Hacienda Resolución) dating from the 1840s, the central at Playa Grande was in operation from the 1870s until the expropriation of its sugar cane fields by the U.S. Navy in 1942. It was founded by the Danish industrialist Matías Hjardemaal, but was sold in 1889 to José Benítez Guzman, who combined it with his other properties to make Central Playa Grande the largest sugar operation on the island. His descendants established the Benítez Sugar Co.

Because the mill used newer technologies than many of the older mills on the Puerto Rican mainland, its massive steam-driven iron rollers greatly increased the quantity of juice pressed from the cane. Furthermore, after the Puerto Real sugar mill in Esperanza failed and was dismantled in 1927, the cane from its fields was trucked to Playa Grande for processing for a time. Thus in 1928 the mill enjoyed its most successful year, producing 13,088 tons of sugar and molasses. While this was not an insignificant output, it is not in the same league as the larger plantations on the mainland. The Guánica mill, for example, produced more than 100,000 tons of sugar annually. Yet the future of this industry on Vieques seemed secure.

However, by 1917 there were more than 90 sugar beet factories operating in 18 American states, producing sugar to compete with the cane fields of the tropics. Later, during the Great Depression, a glut of sugar in the United States forced the imposition of stiff quotas on the industry. This, declining production, and the sometimes-violent local labor unrest forced the Playa Grande plantation into receivership by 1936. Three years later it was sold to Juan Angel Tió, its final owner, who had hopes of turning the property around—until the Navy stepped in, acquiring his cane fields in 1942. The facility was shut down in 1944 and the machinery that could be removed was stripped from the concrete foundations and shipped to Florida where it was installed at a mill near Belle Glade. Ultimately this mill also failed and what remained of the Playa Grande equipment was sold to a company in Cuba.

Throughout the British and European colonies of the West Indies the forced labor of imported African slaves fueled the sugar industry. In 1845 for example, chattel slavery supplied more than 80 percent of the labor for the industry around Ponce, Puerto Rico, at a time when there were nearly 800 sugar plantations on the island. During the same year, in Vieques, 36% of the population were enslaved workers whose labor powered the nascent sugar industry. However, by the time of emancipation in Puerto Rico in 1873 there were only 33 enslaved persons remaining in Vieques, mainly domestic workers.

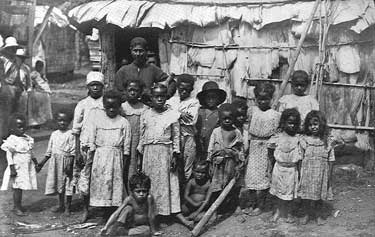

Paradoxically, the plantation owners learned that they could more economically operate their mills by recruiting freed Africans from the British Caribbean—many from neighboring Tortola. These workers, as Protestants, were not subject to the Catholic Church’s strict prohibition of work on Sundays and the many church holidays and thus could work more hours each week. These English-speaking workers—known as cocolos—while freed from legal servitude, were still much mistreated. Just a year after the abolition of slavery in Puerto Rico plantation workers in Vieques rioted due to these systematic abuses. One was killed in the government response.

When slavery was abolished the plantation owners were awarded 35 million pesetas per freed slave. But the “formerly-enslaved” were required to remain on the job for three more years. The plantation house and the preserved production machinery of one such site may be visited today in Manati, west of San Juan.

In early 20-century Vieques there persisted a very difficult life for the field workers—many of them formerly enslaved people from neighboring islands—who supplied the cane for the Playa Grande mill. In some ways, the workers’ lives differed little from the days of forced servitude. The 1901 report from Puerto Rico’s military governor stated, “…the relation between the peon and the planter is practically the same as between master and slave, with a difference in favor of the latter.”

In his 2004 memoir, The Route; The Forgotten Side of Vieques, the author “Pragmacio” paints a vivid picture of life in Playa Grande in the 1930s:

“In the sugar mills during those days, there were four types of housing. There was housing for the technical personnel like electricians, drivers, machine operators, locomotive engineers, plumbers, and others. There was housing for the white-collar workers and professionals, housing for the poorest of workers with no dexterity, and the pranganas that were the quarters for the migrant workers who came from Puerto Rico and other Caribbean islands. These pranganas were of a very poor appearance. They were long buildings with no rooms. Some of the workers used to put old sacks or pieces of cloth to make a separate room on their own. They were of such a bad look that when people were in a bad economic condition they used to say, “I am in the prangana.”

Down to the west of La Central and towards the south, there was a street named the street of Fire. It was a dirty street, covered with soot. All the houses were covered with the soot that was produced at La Central, coming out through the chimneys into the atmosphere. I noticed that the faces of almost all the people who lived there were covered with that black soot. The poorest people in this neighborhood lived on this dirty street in shabby houses.”

Click the red hotspot to enter this structure, once a ground-floor storage room underneath a large factory building, now collapsed. Once inside, look upwards to note the termite trails on the ceiling.

There was work for all during the sugar cane harvest, the time known as Zafra (harvest). The tall stalks were cut by workers wielding machetes all day in the hot sun and loaded into ox carts before being dumped into flatcars on the narrow-gauge railroad lines that ran from the cane fields to the mill. The eight locomotives of the Playa Grande mill also delivered the processed sugar and molasses to the dock at Punta Arenas, on the island’s northwest coast. After the harvest the same workers needed to manually clean and cultivate the fields with hoes, before planting the seed-cane for the next crop and adding fertilizer.

But after the time of Zafra came to an end, the period of Bruja (the “witching,” or the “dead season”) began. There was no work to be had, and those who had not put enough away, or had no vegetable garden to tide them over entered a painful season of poverty and hunger. These fieldhands had few options in Vieques. The Benitez family, owners of the Playa Grande mill, held title to 44% of the island’s property. Together they and another ownership group controlled 71% of the arable land, one of the most extreme case of land monopolization in Puerto Rico. The Census of 1899 found that nearly 86% of Vieques families were landless. Thus, the economic reality was a bleak one for the workers, who were forced to endure whatever was required to survive. As the author Pragmacio explains:

“In those days the foremen were the only people allowed to carry a gun on their waist. They also carried a dagger and a long machete or sword hanging from their waist. They used that machete to blast them on the back of the workers to make them work more or faster. The workers were much abused. They were very obedient in order to avoid trouble and continue making a living, even at the expense of being abused. During those days workers had to work from dawn to dusk.”

Shortly before the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor in 1941, with war on the horizon, the US Congress approved the initial funding for military base construction on Vieques. In the ensuing months life markedly changed for the Playa Grande central owners and more drastically for the hundreds of workers—sharecroppers, or agregados—who depended upon the sugar cane harvest for their livelihoods.

After the Navy seized great swaths of the island, three thousand Viequenses either left voluntarily or were moved to the makeshift resettlement towns of Santa Maria and Monte Santo. As Pragmacio wrote, “The demolition of buildings and houses was occurring. I saw how the bulldozers were tearing down the houses with all the personal belongings inside. People were forced to leave fast, otherwise they could lose everything.”

Over the next six years the Navy acquired two-thirds of the island’s 52 square miles of land. According to some sources, the Navy would have preferred depopulating the entire island for its own purposes, forcibly removing the residents to St. Croix.

With the land expropriation, both the wealthy plantation owners and the owners of the more modest island homesteads were provided some compensation. But most of the workers—the tenant farmers—had no recognized right to their homes, even though many had lived on and cultivated the land for generations. They received no compensation. Some with the required skills obtained temporary construction jobs with the military. However, as UCLA Professor of Sociology César J. Ayala noted “…[In 1943] construction practically came to a halt….and the effect of the expropriations finally hit home as the future looked bleak, there were no jobs, and there was no land.”

In his memoir, Pragmacio describes the sense of injustice and alienation the expropriations created:

“The Navy installed a cable across the road between Andino and La Hueca, from a tree to a fence pole….This was a checkpoint where everybody, including pedestrians, passenger cars and buses, had to stop and be checked for identification.…Many residents couldn’t believe that strangers from other places treated us as strangers on our own land. They could drive and walk around the island freely, but the people who were residents, who were born and had lived in Vieques forever, were treated like enemies.”

In the 1920s, Playa Grande had 17 miles of tracks, seven locomotives, and numerous cane cars. All the locomotives were sold for scrap except this badly-corroded specimen.

Drag downwards to note the train tracks in the left foreground. Click the red hotspot to see a closer view of the locomotive remnants. Then drag within the image to rotate the view.

World War II ended with the surrender of Japan on September 2, 1945. In Vieques, where the six years of war saw a disastrous disruption of the island’s traditional way of life, there was hope and the expectation that the Navy would soon withdraw, and the island’s economy would be reborn. This renaissance, however, would not be realized for nearly another 58 years. Instead, as the Cold War intensified, the Navy acquired additional land on the island, totaling some 20,660 acres, which later became the Marine base Camp Garcia. The new takeover of Vieques was sealed in 1947 when the Navy built up the Roosevelt Roads harbor and airport in nearby Ceiba on the east coast of the Puerto Rican mainland. This created one of America’s most important training installations: the Atlantic Fleet Weapons Training Facility. The U.S. armed forces began bombarding Vieques for target practice from the sea and the air. There were amphibious landings by tens of thousands of sailors and marines on the island’s beaches, the same beaches today enjoyed by tourists from around the world.

But earlier, in the the immediate aftermath of WWII, when the rebirth of the island seemed imminent, the young Pragmacio visited the remnants of his home and the Playa Grande sugar mill, then as today taken over by the relentless jungle:

“The Second World War was over….Now we could go back to the lagoon, to the hills of Ventana, to the remains of Playa Grande, to the beaches of Mosquito, to Playa Vieja and to the fishing areas on the western beaches. Now we could go hunting wild pigs and goats. We could go for fruits and for firewood, so much needed in our homes. Now we could go hunting crabs on the mangroves of the lagoon and collect coconuts in the forests around the lagoon.

“We got up early before dawn one morning and took off through the hills of Andino, went across the navy’s barbed wire fence and continued down to the Playita area. We walked to El Sapo, the place where I was born. There, we found the remains of the houses all crushed down and lots of metal sheets all corroded by time and humidity, as well as lumber all eaten up by termites and deteriorated with time and smashed down when the navy bulldozers destroyed them. My former house was there, lying in pieces on the ground.

After looking at that sad picture we walked down to La Central….It was difficult to distinguish anything. The machine shop was not there but the concrete floor remained almost untouched. The stone walls were there and the remains of La Central.

“We immediately ran into the locomotives parking area. What a surprise! The eight locomotives were right there! They were all covered up with grass and vines and dust.

Luis ran around looking for No. 8. It was his father’s machine. When he found it we immediately started to remove all the grass and vines that covered the machine. He sat on the driver’s stool and pretended to be his father….That was fun and happiness for us. We walked around the other machines, looking all over for whatever we could find to take as a souvenir. The smell of molasses was there. I was told that the smell of molasses would stay there for years and years.”

In 1941-42 Jack Delano, working for the Farm Security Administration, made photographs of several sugar plantations in Puerto Rico. Although there is no evidence that Delano visited Vieques during that period, the way of life at Playa Grande was likely similar to that shown in the gallery of his images below. (Library of Congress)

Epilogue

In time the Navy claimed three-quarters of Vieques, using the western section for its ammunition storage and the eastern section for its bombing and troop landings. The people of Vieques were squeezed into the small strip of land separating the two military areas. Over the next four decades, the Navy bombed Vieques from the air, land, and sea. In 1998 alone, the military dropped 23,000 bombs on Vieques. In addition, artillery from ships and tanks often deployed armor-penetrating and cancer-causing depleted-uranium rounds.

A significant local opposition movement in Vieques was active by the early 1980s. However, it wasn’t until a tragic event in 1999—errant bombs killed a civilian working for the Navy—that the ensuing years of protest, which garnered international attention and support, ultimately forced the military to vacate the island and the mainland Roosevelt Roads naval base in 2003.

Vieques faces many years—perhaps generations—of methodical inch-by-inch inspection and decontamination of the land and water where unexploded munitions and toxic depleted uranium remain a hazard. Dr. José Seguinot Barbosa (Department of Environmental Health, University of Puerto Rico) observed that the eastern tip of Vieques has “more craters per kilometer than the moon.” Fortunately for the new economy of the island, the majority of the desirable tourist beaches on the island’s southeastern coast have been sanitized, as long as one remains on the marked pathways (see trail sign, above right).

Now the people of Vieques have a new concern: the invasion of Airbnb.

Sources and Acknowledgements:

Tours of the Playa Grande Sugar Mill ruins are conducted, usually on Saturdays during the tourist season, by the Vieques Conservation and Historical Trust (VCHT). The lead tour guide, Robert Marino, is an extremely knowlegable local historian. You can contact VCHT for tour information and reservations at 787-741-8850 or viequesconservationtrust@gmail.com.

Some may find the paths through the ruins challenging as it snakes around vines and sprawling tree roots. If visiting on your own consider extending your stay and hiking the beautiful trail from the ruins down to the Playa Grande beach.

Archival images are from the Farm Security Administration (FSA) Jack Delano collection at the Library of Congress (LOC) and from a research website of Universidad Interamericana de Puerto Rico.

Pragmacio. The Route: The Forgotten Side of Vieques. Athena Press, 2004

Pragmacio Rivera Santos. 11/18/1934 – 11/9/2007

Arbona, Javier. “Vieques, Puerto Rico: From Devastation to Conservation and Back Again.”

Ayala, César J. “From sugar plantations to military bases: the U.S. navy’s expropriations in Vieques, Puerto Rico, 1940-45.”

Grusky, Sars. “The U.S. Navy and Vieques, Puerto Rico: Conflict and Coexistence.”

Pelet, Valeria. “Puerto Rico’s Invisible Health Crisis.”

“Puerto Rico Sugar Plantations and Sugar Mills.”

Wittner, Lawrence. “Breaking the Grip of Militarism: The Story of Vieques.”

“Sugar and Slavery in Puerto Rico: The Plantation Economy of Ponce, 1800-1850.” (Review)

Many thanks to Robert Marino of the Vieques Conservation and Historical Trust for his helpful suggestions.

A personal note: I’ve always been fascinated by ruins and the evidence of prior civilizations. One of my research projects concerns the ancient monuments of Ireland.

Angela Amoroso

Posted at 04:46h, 26 FebruaryQuite informative and thought provoking! One has a tendency to think of Puerto Rico as an “island in the sun” without a history of its own – nor that there are other smaller islands with an amazing story to tell. Thank you Howard for sharing with us these stories and images from the tiny island of Vieques.