14 Feb Airmail Arrow

“Erection of a two million candlepower beacon, the first of the airway beacons in Nevada, started yesterday near Verdi on top of the mountain above Mogul between Reno and Verdi. A fifty-one foot tower for the huge light was taken to the bottom of the mountain this morning by truck, and with tractors was hauled as far as the ditch which runs along the side of the mountain….Twenty-six lighting units will be installed between Verdi and Battle Mountain…Six emergency landing fields between here and Battle Mountain will be lighted and the huge beacons will be placed on high mountains all along the 225-mile division.”

Reno Evening Gazette, Tuesday, July 31, 1928

Click the red hotspots to explore three different views of Reno’s Airmail Arrow in virtual reality.

According to the story in the Reno Evening Gazette, some 30 men labored to drag the steel tower over the Steamboat Ditch and move it into position atop a newly-poured concrete arrow on this hill above Mogul at the end of July in 1928. Read the story in its entirety here.

Now, the tower, its beacon and service building are long gone. All that remains is the concrete arrow, once painted a brilliant yellow so that it would be noticed by the pioneering aviators day and night. The 57-ft long arrow is still complete, but its concrete is now broken into more than 18 pieces by nearly a century of exposure to Nevada’s temperature extremes, plus the unstable ground of the narrow ridge, where the tail end of the arrow has already been undermined.

Northern Nevada played an important role in the rapid evolution of communications technologies in the 19th century. From April of 1860 until November of 1861, the Pony Express delivered mail from Missouri to California at the blazing speed of 10 days, following a trail in Nevada that roughly parallels modern US 50. When the telegraph spanned the continent in October 1861, the Pony Express became a dusty, if romantic, anachronism. When the Transcontinental Railroad reached Reno in 1868, it would soon become possible to send all sorts of letters and packages through the U.S. Mail using its Railway Post Office cars.

Soon after the Wright brothers made their first flight in 1903, the next communications revolution was about to begin. By 1918 the east coast of the U.S. had some limited airmail service. Navigation, however, was primitive, as pilots had to look for landmarks, such as railroads and natural features. Flying by night was especially fraught with danger.

But Reno also had an important role in this technological leap when Congress in 1923 funded the Transcontinental Airway System, with its bright rotating beacons on a 50-ft tower and brilliant yellow or orange concrete arrows. Airmail pilots in their open-cockpit biplanes could simply look down to follow the lights and arrows by day or night. The brilliant beacon, on a clear night, might be seen from 40 miles away.

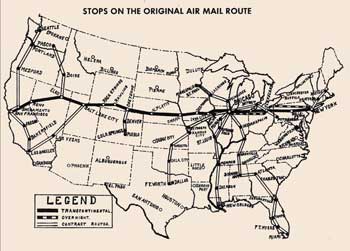

Initially the route—including Nevada—stretched straight across the middle of the nation. But by 1933 the system’s 1500 beacons spanned 18,000 miles, with contracted routes branching north and south from the pioneering west-east path. Two sections traversed Nevada, the initial route linking Chicago and San Francisco, with its Nevada airmail depots in Reno and Elko. Later, a second route linked Los Angeles with Salt Lake City, with its Nevada depot in Las Vegas.

Each arrow pointed to the next waypoint. West of Mogul, the arrow located at Donner Pass, with its tower intact today, pointed to the Mogul Arrow. To the east of Reno, the next arrow was located on a hill above Lockwood.

Each beacon had a set of red or green lights below the white beacon; these flashed in Morse Code to indicate the beacon’s identification on the route. In addition to the arrows and beacons every 10 miles, lighted emergency airfields were funded along the route, spaced every 15 to 20 miles. The first beacons were illuminated by acetylene-gas lamps, fed by fuel stored in a shed at the base. Later versions used a generator or a electrical-grid relay in the shed to power a special electric bulb in the beacon.

By the mid-1930s, however, the system was becoming obsolete following the introduction of Low Frequency Radio Range (LFRR) beacons. Further improvements in radios and instrumentation doomed the concrete arrows and lighted beacons; most of the towers soon became scrap metal for the war effort.

Reno’s site, featured in the virtual-reality sequence at the top of this page, was designated “18 SF-SL Mogul,” site No. 18 on the San Francisco–Salt Lake airway. The route was established on September 8, 1920, and flown, beginning in February of 1921 by official U. S. Post Office pilots.

The most celebrated of the pilots on this route was William Blanchfield, an Irishman who served in the British Royal Air Force during WWI. He was hired to fly the Reno–Elko leg of the airmail service in 1923. Tragically, he died when his aircraft crashed on Ralston St. in Reno the next year. Reno’s first airport, opened two miles south of downtown in 1920 and first known simply as Reno Air Mail Field, was renamed in his honor. The aviator’s last name became two words; the airfield is shown on period maps as “Blanch Field.” The location soon proved too small for the newer generation of aircraft, and by 1933 the land was used in the expansion of the Washoe County Golf Course. Blanchfield’s memory, however, is kept alive by the local Irish heritage group, Sons and Daughters of Erin, whose members leave an Irish shamrock on his grave each year around St. Patrick’s Day.

If you would like to visit Reno’s surviving reminder of the Transcontinental Airway System, the Mogul Arrow can be reached from the trailhead and parking area off White Fir Dr., just after it crosses the Truckee River. Take the Tom Cooke Trail counter-clockwise up the hill to where it meets the Steamboat Ditch Trail. This is also known as the “Hole-in-the-Wall Trail.” Proceed west to the tunnel—the “Hole in the Wall”—under a ridge. From there climb the steep road up to the top of the ridge, and then turn right (north) to follow the ridge to the arrow. This is about a 6-mile round trip hike, with a 500-ft elevation gain. The Mogul Arrow may be seen here on Google Maps. Other arrows and beacon sites in Nevada may be viewed here.

No Comments