08 May Ash Meadows National Wildlife Refuge

Walking on a boardwalk suspended above a parched and bleached alkaline desert landscape is reminiscent of a scene from science fiction. You are a visitor to another dimension, magically allowed access on a walkway intruding through a wormhole.

These other-worldly aspects are confirmed when the boardwalk crosses a narrow gurgling stream flowing underneath, its margins supporting a flourishing micro-climate of plant life. Walking further, the stream suddenly widens and deepens into the mesmerizingly blue, 15-feet-deep Crystal Spring, with its clear 86°F waters rushing up from its fossil aquifer at the rate of 2,800 gallons a minute.

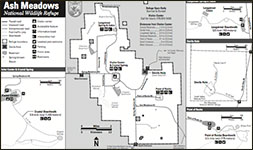

The 23,000-acre (36 sq mi) Ash Meadows National Wildlife Refuge, in the Amargosa Valley of southwestern Nevada, is about 90 miles northwest of the Las Vegas Strip. Even though it butts up against the popular dunes and vistas of Death Valley National Park, it receives only a small fraction of the tourist traffic of its better-known neighbor. It does, however, share a peculiar naming convention with Death Valley. There, early publicists took cues from the baked landscape and the infernal summer heat and consulted their inner Dante for place names such as Devil’s Cornfield, Devil’s Racetrack, Devils’ Throne, and Devil’s Golf Course.

Ash Meadows contains Devils Hole, a 40-acre detached parcel of the national park, and a forbidden portal to another world. This can be explored in a panoramic view below, left. Click here to see Devils Hole in a satellite view.

Touch here for the handheld version. Touch here for the HMD (Google Cardboard) version.

The Devils Hole portal proved to be tragically one-way in 1965 for two Las Vegas brothers-in-law. Wriggling under the fence protecting the site, four scuba divers attempted to explore the passages extending down from the 8-by-60-foot opening to the abyss. Two of them would never be seen again after that night. Their remains likely rest on the still-to-be-reached bottom of the chasm, which subsequent—and better prepared—divers determined is at least 500 feet below the surface. Some evidence suggests that Devils Hole may in fact have no defined bottom at all, with an effectively infinite connection to other subterranean water systems. In 2012, a fortuitously videotaped Devils Hole tsunami resulted from a 7.2-magnitude earthquake 2,000 miles away, in Oaxaca, Mexico.

On April 30, 2016, a trio of Nevada ne’er-do-wells, including a convicted felon, perhaps inspired by the vanished divers from a half-century earlier, used a gun to blast the security cameras and break into the Devils Hole protected area. Nearby were empty beer cans and a pool of vomit. No scuba divers these clowns, but at least one of them was wading in the shallow water of a rock shelf, where his boxer shorts were later found floating. Also discovered floating in the shallows was a dead Devils Hole pupfish (Cyprinodon diabolis), the rarest fish in the world.

At the time of this 2016 intrusion, there were only 115 of the species remaining. Suddenly there were 114, after the vandals stomped upon the life-sustaining shallow rock shelf at one end of the cave mouth. Park officials later noted that since “April through May is the peak spawning season…the intruder likely crushed and destroyed eggs on the shelf.”

This 19-by-9-foot area, only a couple of feet under the water, is the remnant of the long-ago collapse of what was once the roof of a cave. When that occurred, some 60,000 years ago, what had been a dark and lifeless environment was for the first time exposed to the sun. The roof collapse enabled photosynthesis in the 92.3°F water, creating the algae mat on the shelf that serves as the source of food, and the only hospitable platform where the pupfish might lay their eggs.

Click to view a panorama of Crystal Springs.

Touch here for the handheld version.

Within Ash Meadows are at least twenty-six species of plants and animals which are endemic to the park; they are found nowhere else on earth. Four of them—three fish species and one plant—are considered endangered. This concentration of locally-specific plants and animals puts Ash Meadows at the top of the list of such places in the United States. Ironically, the name Ash Meadows refers to what was once a dominant feature of the landscape, dense stands of Ash trees. These exist now only in small isolated groves, but the name remains.

If you look closely at the virtual-reality view above, which explores Kings Spring at Point of Rocks, you may be able to spot several Ash Meadows Amargosa pupfish darting about. This is the most abundant of the four endemic fish species found within the refuge; they may also be seen at other springs and streams such as Crystal Spring and Longstreet Spring. The larger males are colored a brilliant blue during their spring and summer breeding season. The endangered Warm Springs pupfish and the Ash Meadows Speckled Dace live in more specialized aquatic habitats, and are less often seen by visitors.

Click to view a panorama of Devils Hole. Touch here for the handheld version.

All the unique biodiversity within Ash Meadows is due to its status as an isolated desert oasis within the parched Mojave Desert. The water that gives life to the oasis begins its journey on mountain peaks more than 100 miles to the northeast, from where snowmelt enters a massive underground aquifer. The origin of the water in Ash Meadows is distant in time as well as location, as much of it has been slowly seeping through the aquifer complex for more than ten thousand years. This Pleistocene “fossil water” enters the Meadows due to artesian pressure at a year-round flow of more than 10,000 gallons per minute. Additional flows are due to one of the world’s longest underground rivers, the Amargosa, which begins with springs near Beatty, and flows southwest for 125 miles, passing through Death Valley Junction, with its Amargosa Opera House, until it terminates at Badwater in Death Valley, at 282 feet below sea level the lowest point in the Western Hemisphere.

That Ash Meadows National Wildlife Refuge exists at all is somewhat of a miracle, as the entire area, already decimated by draining and peat mining, was plotted out for a 34,000-lot subdivision in 1980. The savior of the Meadows, and its special biodiversity, was the Devils Hole pupfish.

Its rarity, its precarious existence, and its inaccessible and deadly environment all have given the fish a charisma which ultimately helped to win the fight for public opinion, gaining protection for the species in 1967, and finally putting an end to the planned exploitation of Ash Meadows with the establishment of the National Wildlife Refuge in 1984. This was not a battle easily won, as business interests in Pahrump answered the “Save the Pupfish” bumper stickers of environmentalists with “Kill the Pupfish” stickers of their own. A newspaper editor in Elko actually suggested in 1976 that someone pour a fish poison into the pool as a way to put an end to the campaign.

The Devils Hole pupfish is so small—only an inch long—that they are impossible to spot from the public catwalk high above the pool. The males are an iridescent blue-grey, while the females feature a drabber olive coloration. Although they may occasionally venture 100 feet further down into the cave system, the pupfish spend most of their short 10-14-month life span foraging and procreating near the shallow rock shelf near the surface.

It is unclear when or how the Devils Hole pupfish made their appearance in this remote location. For many years, the scientific community seemed to agree that the species became isolated and differentiated in that location as recently as 10,000 years ago, and perhaps much earlier. Some recent studies, comparing the genetic diversion of the Devils Hole pupfish from that of its neighbors, the Ash Meadows Amargosa and the Owens pupfish, indicated a genetic split dating back approximately to the era of the collapse of the cave roof.

But while the other species of Ash Meadows pupfish evolved in the receding waters from the large lakes and rivers that covered the area 10,000 years ago, this cannot account for the species in Devils Hole, as the cave’s mouth is located above the level of the ancient lakes. Was there once an underground pupfish passageway linking Devils Hole to one of the other pools nearby? Limited oxygen levels below depths of 125 feet would seem to make that unlikely. Did the odd Ash Meadows Amargosa pupfish escape from the bill of a bird flying overhead, tumble down into the tiny target of the Devils Hole pool, and somehow find a mate similarly transported, and thus begin the process of their isolated evolution?

Author and artist Kim Stringfellow, in her beautifully written and extensively researched essay Divining Devils Hole, suggests a more reasonable explanation: Native American children made a game of transporting the pupfish from another pool in Ash Meadows up into Devils Hole. In fact, other studies have suggested that the unique characteristics of C. diabolis may have occurred much more rapidly than previously presumed. If this is proven to be the case, perhaps the children were playing their move-the-fish game that resulted in the Devils Hole pupfish less than a few hundred years ago.

While there are picnic tables for visitors at several locations in Ash Meadows, the only aquatic recreation available is at Crystal Reservoir, where swimming and non-motorized boating are allowed. Swimmers, however, should be aware that the warm waters often result in “Swimmer’s Itch” (schistosome cercarial dermatitis), caused by the larval stage of a flatworm boring into the skin. This is not contagious, nor life-threatening, but can be very bothersome.

Much more dangerous, threatening our lives from beyond the wormhole, is the fossil water now lingering in a labyrinth 40 miles to the northeast, underneath the Nevada Test Site. There, below the atom-bomb-scarred sands of the desert, water rests in pools of radioactive detritus. In another 15,000 years, it will slouch its way into Devils Hole, pupfish be damned.

Thanks to Kim Stringfellow and her Divining Devils Hole essays, part of her continuing Mojave Project for the inspiration for this page. Thanks also to Sydney Martinez at TravelNevada, and the Ash Meadows National Wildlife Refuge.

Bonnie Doyle

Posted at 08:49h, 01 NovemberI used to swim in the Crystal spring, Longstreet spring, and Fairbanks spring when I was a kid during the late 70s and early 80s. We even swam in devil’s hole when you could enter from a cave around the backside. My brother and I caught a few pupfish and took them home but my mom mad us take them back and we did. I learned to waterski on crystal lake when you could put motorized boats in the water, and I won first place in a bass tournament back in 2002, when you could still fish the lake for large mouth bass. Those pup fish have managed to survive thousands of years with no help from humans. I don’t understand why park officials had to drain our lake to get rid of all the “nonindigenous ” wildlife when the lake or reservoir itself is not indigenous, but is a man made body of water. We respected the no swimming rule when they enforced it at the springs, but to take away the boating and fishing rights at Crystal lake when there are no pup fish in the lake was going overboard. That was the only summer recreation for us long time locals. They say we can still swim the lake, but in the summer months they drain it so low that it makes the mud around the water so soft you sink up to your knees in it, and it causes the flying knats to come out in huge numbers. The swimmers itch is also far worse when the water is low. They do this on purpose so that locals will stop swimming the lake. Im all for protecting an endangered species. But the springs feed the man made reservoir…. and therefore the pupfish are in no danger from anything that happens in the reservoir . For years there were beautiful small and large mouth bass in the reservoir that provided locals with a place to take their families to fish and swim. But they drained the reservoir to kill off the bass so people wouldn’t come to fish. Do they not think that maybe some of the migratory birds eat bass too ? I’ve seen three bald eagles and many many golden eagles over the years there. Do they not eat fish? Environmentalists seem to always go too far and often to the point of inadvertantly making things worse for the very wildlife they set out to protect . I just wish they could have left the damn reservoir alone, since it was in no way a danger to the pupfish. Now I have nowhere to take my grandchild to swim and fish the way I did many years ago. So much for preserving a way of life for us humans.

Denny Scharringa

Posted at 07:37h, 08 SeptemberI dove in Devil’s Hole In the late 50s, making a film that was supposed to be for I search for adventure TV show. Bob Lorenz headed up the dive along with Jim cutting a photographer and diver and also Bob Howell who owned Mar Vista rentals myself and Johnny Bender and Pete Dotson help with a lighting. Also Bob’s wife Trudy was in the film and Bob house wife as well

Diego

Posted at 13:39h, 10 DecemberGreetings

I need to know which company carries out mining activities in the area for a study about ramsar sites.

Thank you so much.

Best regards,