29 May Where the Pavement Ends

Washoe County, Nevada

Where the Pavement Ends Begins Nevada’s Serengeti.

— Erik Holland

Only 20 miles north of downtown Reno is found a remarkable landscape, a living monument to the Old West of buckaroos and Hollywood romance. The Warm Springs, Palomino, and Dry Valleys, bisected by Winnemucca Ranch Road, are towered over by the 8,700-ft Tule Peak, the highest prominence in the Virginia Mountains and a site sacred to Native Americans. The pavement ends 4.2 miles after the road leaves the busy Pyramid Highway and then enters a multi-use landscape of working ranches, BLM rangeland, and recreational resources for everyone from Sierra Club hikers to ATV enthusiasts and glider pilots. Its many hills and valleys are populated by widely-spaced “horse properties,” by large corrals of cattle, by herds of antelope, and by hill-climbing 4x4s traversing the Moon Rocks of the adjacent Hungry Valley. On this page you will learn of the ongoing threats to this landscape, and how you can help to protect it.

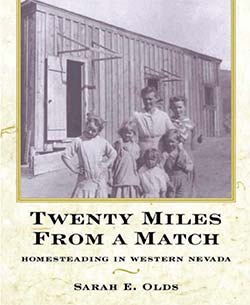

In the virtual-reality environment (below) there are 21 different nodes, or VR locations, all linked together with red hotspot targets. As you explore, look for the tour of the Marshall Ranch and its uplands, the Moon Rocks recreation area, and the corrals of the Winnemucca Ranch. You will also encounter a detailed exploration of the site of the Olds Homestead. This was the setting of the book Twenty Miles from a Match, Sarah Olds’ lively and engaging account of her struggles to recreate the pioneer life in early-20th-century Nevada, north of Reno, where the pavement ends.

Click and drag to explore some of the features of the landscapes bordering Winnemucca Ranch Road. The VR environment will lead you to the Marshall Ranch and its uplands, the site of the Sarah Olds Homestead (Twenty Miles from a Match), and the Winnemucca Ranch itself. A version of the tour optimized for a handheld device is here. The VR experience begins high above the spot “where the pavement ends.”

Reno artist Erik Holland, celebrated for his plein aire landscapes of wild Nevada, painted Where the Pavement Ends in 2018. Its subject, the dramatically illuminated and imposing southern face of Tule Peak, may be seen from a drone’s perspective in one of the VR nodes above.

The title of the painting not only reflects a particular fact on the ground, but also serves as a meditation on the complex tension that exists where a city abuts its wild next-door neighbor. Holland’s quote (top) describing this panorama as “Nevada’s Serengeti” encourages us to imagine this area, so close, accessible (and vulnerable) to Reno, as a place worth protecting. See a brief video of the artist at work (left), excerpted from Rainshadow, by Kari Barber.

Winnemucca Ranch Road was once a main route into California. The remnants of a stagecoach stop may still be seen at the Marshall Ranch. Near Pyramid Highway stood the Twenty Mile House, another stagecoach stop dating from the 1860s, which at different times featured a restaurant—and a bordello. A character known as Whiskey Annie worked there, and, the story goes, kept a six-shooter in her garter and used it to do away with four of her husbands.

While there is nothing of the house remaining, it figures prominently in Twenty Miles from a Match. Its location is indicated in the VR node where Winnemucca Ranch Road intersects with Pyramid Highway.

This area of “Nevada’s Serengeti” was best known in the past for its large herds of wild horses, many of whose descendants are now awaiting adoption at the nearby BLM holding facility. At one time the horses roaming these valleys were part of the largest herd of wild mustangs in North America. Buckaroos working the local ranches, as well as Reno-based wranglers looking for some extra cash, would herd the mustangs into dead-end enclosures. The proud animals, descendants of escaped or abandoned working horses, would end up as dog food and glue at a gag-inducing rendering plant on Wells Avenue.

This practice was ended by the Wild Free-Roaming Horses And Burros Act of 1971. However, the mustang roundups were immortalized in the epic (or epically disastrous) 1961 film starring Clark Gable and Marilyn Monroe, The Misfits. This was the final film for both of these Hollywood superstars. See the video to the right.

The VR tour proceeds northwest, following Winnemucca Ranch Road, past its sprawling eponymous ranch corrals, past the ominous Washoe County sign indicating the spot where road maintenance ends and you may need to switch your vehicle into low 4WD—or turn around. However, before you approach the steep and deeply-rutted hill, the trailhead for the remarkable McKissick Canyon presents itself, a landscape epitomizing the BLM’s mission to support diverse uses of public land resources. On this 3-mile, 2,000-ft elevation-gain trek through a wonderland of changing rock formations approaching the dual peaks of the Dogskin Range, you may encounter herds of cattle, antelope, deer, and the occasional ATV rider. The VR tour on this page ends at this trailhead, but the entire McKissick Canyon hike is presented as a virtual-reality environment on a different All Around Nevada page.

A warren of otherworldly-sculptured smooth rock formations, known as the Moon Rocks is featured in the VR tour. This is the key draw of the Hungry Valley Recreation Area, accessed from a crossroad some 6.2 miles in from Pyramid Highway. This area was designated as an open Off-Highway Vehicle Area by the BLM in 2001. If this landscape were in a national park (or in California) it is likely that there would be limited vehicular access to the rocks to protect and maintain the scenic resource for future generations.

But since this is Nevada, there is room enough (and official sanction) for every kind of recreation. Thus, some weekends there may be more than a dozen camping trailers, some the large and luxurious “toy haulers.” By day these RVs disgorge their Mad Max ATV vehicles, from mini-trailbikes for the budding Max Jr., to extreme tricked-out UTV (Utility Terrain Vehicle) rock crawlers. These ascend the slick granite Moon Rock formations with a gravity-defying roar. See the video to the left.

This is a desert landscape, where access to its precious aquifers means survival for wildlife, and success for people who try to make a living here. The historic Winnemucca Ranch is now run by Buckhorn Land and Livestock, LLC., which owns or leases much of the pastureland suitable for raising cattle in these valleys, including the nearby Marshall Ranch. In the aerial nodes of our VR tour, you can identify the aquifers by the vibrant patches of green on the surface, representing the rangeland where cattle can thrive.

A small corner of the Winnemucca Ranch has been fenced in and designated as a “conservation easement,” forever protected from development. Included in this easement is a verdant tree-shaded enclosure that holds an important memory for the many descendants of Sarah Olds, and for the thousands of readers who have been captivated by her memoir, Twenty Miles from a Match. This is the location of the Olds Homestead, the place to which Sarah Olds (1875-1963) relocated her family from the bustling city of Reno in 1908 to experience the pioneer spirit of early Nevada. In her compelling little book Olds describes how she struggled with the challenges of raising six children and supporting her husband, who was often incapacitated, through the bitter winters and unpredictable summers of the Nevada high desert.

The family began its homesteading in the horse and buggy era, and continued it into the automobile age, as well as the era when some neighbors opened “dude ranches” to cater to those seeking the “Reno cure.” The family raised chickens, shot and sold gamebirds, grew hay and other crops, and made most of its own clothing. One son, Edison, became adept at trapping coyote, and greatly supplemented the family income with the sale of their pelts. During our field research we were fortunate to have the company of painter Vivian Olds, a granddaughter of Sarah Olds.

Although the Olds cabin and its attached one-room schoolhouse were lost to fires during the 1970s, our VR exploration of the site reveals a number of artifacts that have survived, including a stove and the frame of a wagon. These may be seen as pop-up images in the VR tour. Other surviving remnants of the homestead may be seen in the gallery (above). You may read here an excerpt from the book, in which Sarah Olds confronts a very stubborn rat, and is threatened by a flash flood. Click on the book cover to the right. The book is available for purchase here.

Survival of the Olds Homestead and its relics is not guaranteed, although the remote location of the site, a mile from Winnemucca Ranch Road, does offer some protection. Survival of the larger landscape, these valleys that Erik Holland knows as “Nevada’s Serengeti,” is less certain.

When the Winnemucca Ranch was last on the market, prior to its acquisition by Buckhorn, part of the sales pitch enthused that “This offering includes … long term approval for a 5,000 home master planned community, making it virtually the largest holding acreage proximate to the Reno/Sparks area.” This mother of all Nevada leap-frog development proposals raised alarm bells throughout the local environmental community. If completed, the project could have seen 5,700 acres of Winnemucca Ranch transformed into a upscale community of 23,000 people living in 12,000 homes.

Opposition to the project included activists from the Nevada Land Trust, the local Sierra Club, the Progressive Leadership Alliance of Nevada (PLAN), and others, such as Voters for Sensible Growth, who sought to convey the landscape’s scenic value to the larger community. Artist Erik Holland suggested, “…[the landowners] want to develop their land for money so…we find some money and then the problem is solved. Then there’s no problem anymore! We basically have a national park, a national treasure right here, in our backyard.”

When enabling legislation for the project was being debated in 2007, environmentalists protested at the state capitol. One activist was quoted in the Reno News and Review:

“I remember it being so open,” she said. “I remember wild horses. I remember we would go, and there’s a little ranch down the street, and we could watch the wild horses run. And we could go for hikes and see their tracks. It wasn’t city, it was open, like you were free, yet it was fairly close, but at the same time out there, and just, like, unimaginable—like blues and purples.”

There is a natural synergy between plein aire painters and the environmentalist community. The political context of Holland’s paintings, as well as those of Judy Hibish, were detailed in a 2013 article on the website of PleinAir magazine:

“The artists conducted ‘paint-ins,’ a tongue-in-cheek term that echoes ‘sit-ins’ and that simply means they painted on the coveted property. The Nevada Land Trust…helped stage art shows exhibiting work done on local lands, with a portion of the proceeds going to the trust.”

As the community grew more informed about the scenic and historical value of the property, and learned about the problems inherent to leapfrog development sprawl, the county responded by purchasing some of the land. The Nevada Land Trust also obtained some of the ranch, but, more significantly, it brokered deals that allowed the major land owner to create easements to keep much of the open space from development, but also to provide for its maintenance.

As PLAN Development Director Bob Fulkerson said, “Once they develop that Winnemucca Ranch, it’s gone forever. Once they cut down the old growth, it’s gone forever. We can stop them right now on those issues, but next year, yeah, they could be back. But, you know what? It’s our watch that matters. The next generation—it’ll be up to them. They’d better freakin’ be up to the challenge.”

The struggle to keep Nevada’s Serengeti in its wild state continues. A new proposal for re-zoning 1,089 acres in the Warm Springs area to build 187 homes was denied by the Washoe Planning Commission in early 2019. Maintaining public access to the treasures of the place where the pavement ends will require more people to get out there and experience it for themselves, and come to appreciate its value. Please…get out there.

No Comments